From Her Art Exhibit 2019 El Pueblo De Los Angeles

| Los Angeles Plaza Historic District | |

| U.South. National Register of Historic Places | |

| U.S. Historic district | |

| Los Angeles Historic-Cultural MonumentNo. 64 | |

La Placita Church | |

| | |

| Location | Los Angeles, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°3′25″N 118°14′16″W / 34.05694°North 118.23778°W / 34.05694; -118.23778 Coordinates: 34°3′25″N 118°14′16″W / 34.05694°Due north 118.23778°W / 34.05694; -118.23778 |

| NRHP referenceNo. | 72000231[1] |

| LAHCMNo. | 64 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 3, 1972 |

| Designated LAHCM | April ane, 1970 (as 'Plaza Park') |

El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument, as well known equally Los Angeles Plaza Celebrated Commune and formerly known as El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Land Historic Park, is a celebrated district taking in the oldest section of Los Angeles, known for many years as El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles del Río de Porciúncula. The district, centered on the sometime plaza, was the city'south center nether Castilian (1781–1821), Mexican (1821–1847), and United States (later on 1847) rule through most of the 19th century. The 44-acre park area was designated a state historic monument in 1953 and listed on the National Register of Celebrated Places in 1972.

Historic images [edit]

-

Inscription on historical marker "El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Ángeles - Felipe de Neve - September 4th 1781"

-

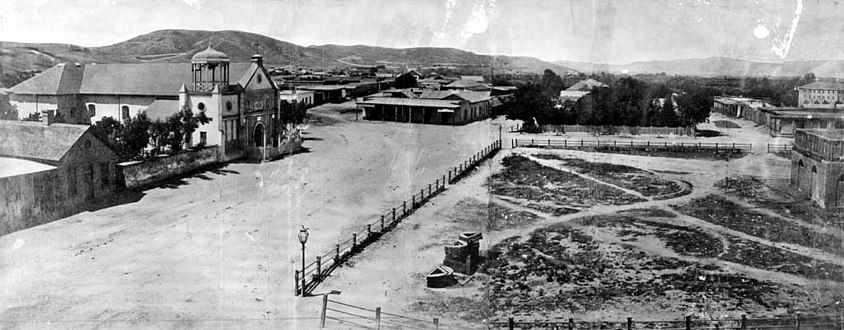

Plaza in 1869

-

Los Angeles Plaza (1876)

-

The Lugo Adobe (built 1840s, demolished 1950s) long anchored the due east side of the Plaza

-

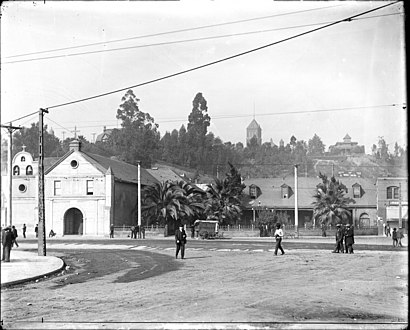

Los Angeles Plaza (c. 1905)

-

The One-time Plaza around 1930

History [edit]

Founding of the Pueblo [edit]

A plaque across from the Erstwhile Plaza commemorates the founding of the city. It states: "On September 4, 1781, eleven families of pobladores (44 persons including children) arrived at this identify from the Gulf of California to establish a pueblo which was to become the Urban center of Los Angeles.

At least ten (and up to 26) of the 44 were Black.[two] [iii]

Spain also settled the California region with a number of African and mulatto Catholics, including at to the lowest degree ten (and up to 26)[2] of the recently re-discovered Los Pobladores, the 44 founders of Los Angeles in 1781.

This colonization ordered past King Carlos Three was carried out under the direction of Governor Felipe de Neve." The small town received the name El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles sobre El Río Porciúncula, Spanish for The Town of Our Lady Queen of the Angels on the Porciúncula River.

The original pueblo was built to the southeast of the electric current plaza along the Los Angeles River and near the Tongva village of Yaanga. Excavations at the church building site "recovered chaplet and other artifacts used during the menstruum of mission recruitment."[4] In 1815, a flood done away the original pueblo, and it was rebuilt farther from the river at the location of the current plaza.[5]

Growth of the Pueblo [edit]

During its first 70 years, the Pueblo grew slowly from 44 in 1781 to 1,615 in 1850—an average of about 25 persons per twelvemonth. During this period, the Plaza Historic District was the Pueblo's commercial and social center.

In 1850, soon after California became part of the U.s.a., Los Angeles was incorporated equally a city. It experienced a major nail in the 1880s and 1890s, as its population grew from 11,200 (1880) to 50,400 (1890) and 102,500 in 1900. As the City grew, the commercial and cultural center began to move s away from the Plaza, along Spring Street and Main Street.

In 1891, the Los Angeles Times reported on the shifting city center:

The geographical centre of Los Angeles is the old plaza, but that has long since ceased to be the middle of population. ... While at once most of the population was north of the plaza, during the past 10 years 90 per cent of the improvements accept gone upwardly in the southern half of the city. ... These are solid facts which it is useless to try to ignore by playing the ostrich acts and level-headed property holders in the northern part of the city are beginning to inquire themselves seriously what is to be done to arrest or at to the lowest degree delay the steady march of the business organisation department from the onetime to the new plaza on 6th Street ...[6]

Preservation equally a historic park [edit]

The 44 acres (180,000 mii) surrounding the Plaza and constituting the onetime pueblo have been preserved as a historic park roughly bounded by Spring, Macy, Alameda and Arcadia streets, and Cesar Chavez Boulevard (formerly Sunset Boulevard). There is a visitors center in the Sepúlveda Business firm. A volunteer organization known as Las Angelitas del Pueblo provides tours of the district.

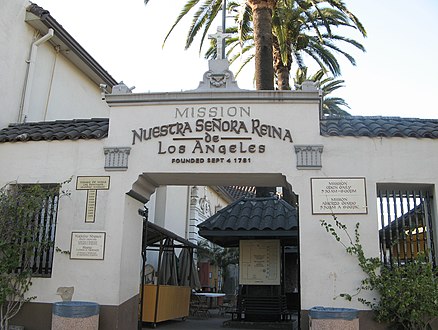

The commune includes the metropolis's oldest historic structures clustered around the old plaza. The buildings of historical significance include Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Ángeles Church (1822), Avila Adobe (1818) (the city's oldest surviving residence), the Olvera Street market, Pico Business firm (1870), and the Onetime Plaza Fire Station (1884). Four of the buildings have been restored and are operated as museums.[7]

In addition, archaeological excavations in the Pueblo have uncovered artifacts from the long ethnic period before European contact and colonization. These include animate being bones, household goods, tools, bottles, and ceramics.[7]

The district was designated as a state monument in 1953,[8] and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. These steps, all the same, did non foreclose the demolition, in the decades to come up, of numerous historic and very old buildings, particularly those that once formed the eastern edge of the Plaza.

Contemporary images [edit]

-

Musicians performing at the Plaza

-

Plaza Church in early 2007.

-

One-time Plaza Firehouse

-

Garnier Building

-

Mural shows of import events

-

Eugene Biscailuz Building and former Methodist Church building HQ, now Mexican Cultural Center

-

Sanchez Street, which runs south from the center of the Plaza's southward side

-

Major sites [edit]

The Plaza [edit]

At the center of the Celebrated Commune is the plaza . It was described in 1982 as "the focal bespeak" of the state celebrated park, symbolizing the city's birthplace and "separating Olvera Street's touristy bustle from the Pico-Garnier block's empty buildings."[ix] Built in the 1820s, the plaza was the city's commercial and social middle. Information technology remains the site of many festivals and celebrations. The plaza has large statues of 2 figures in the urban center'south history: Male monarch Carlos Iii of Spain, the monarch who ordered the founding of the Pueblo de Los Ángeles in 1780; and Felipe de Neve, the Spanish Governor of the Californias who selected the site of the Pueblo and laid out the town. In improver to this, the plaza is dedicated to commemorating the original 40-four settlers (Los Pobladores), and the iv soldiers who accompanied them. A large plaque listing their names was erected in the plaza, and later on plaques dedicated to the individual eleven families were placed in the ground encircling the gazebo in the centre of the plaza.

Buildings on the Plaza [edit]

La Placita Church [edit]

The parish church in the Plaza Historic Commune, known as La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Ángeles (The Church building of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels), was founded in 1814. The structure was completed and dedicated in 1822. The present church, which replaced information technology, was congenital in 1861.[10] The church was one of the first iii sites designated equally Historic Cultural Monuments by the City of Los Angeles,[11] and has also been designated every bit a California Historical Landmark.[12]

Erstwhile Plaza Firehouse [edit]

The Old Plaza Firehouse is the oldest firehouse in Los Angeles. Built in 1884, information technology operated equally a firehouse until 1897. The building was thereafter used as a saloon, cigar store, poolroom, "seedy hotel", Chinese market place, "flop house", and drugstore.[13] The building was restored in the 1950s and opened as a firefighting museum in 1960.

Los Angeles Plaza Park (Begetter Serra Park) [edit]

Los Angeles Plaza Park (besides known as Father Serra Park)[xiv] is an unstaffed, unlocked and open up area within the plaza.[15] It is the site of the demolished Lugo Adobe.[16] In June 2022 protestors toppled a statue of Male parent Junípero Serra, due to Serra'southward role during the colonization of California.[fourteen]

Buildings on Olvera Street [edit]

Olvera Street, known for its Mexican marketplace, was originally known equally Wine Street. In 1877, it was extended and renamed in honor of Augustín Olvera, a prominent local judge. Many of the Plaza District'southward contributing celebrated buildings, including the Avila Adobe and Sepulveda House, are located on Olvera Street. In 1930, it was adapted past local merchants into the colorful marketplace that operates today.

Gallery [edit]

-

Avila Adobe

-

Sepulveda House

-

Facade of Plaza Substation

Avila Adobe [edit]

The Avila Adobe at 10 Olvera Street was built in 1818 and is the oldest surviving residence in Los Angeles. Information technology was built by Francisco Ávila, a wealthy cattle rancher. Its adobe walls are two½ to 3 feet (0.91 1000) thick. U. S. Navy Commodore Robert Stockton took it over as his temporary headquarters when the U.s. first occupied the metropolis in 1846. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the adobe is besides designated as California State Landmark No. 145. Information technology was restored starting 1926 through efforts past Christine Sterling, and at present stands as a museum.[17]

Sepulveda House [edit]

The Sepulveda Firm at 12 Olvera Street is a celebrated residence built in 1887 by Señora Eloisa Martinez de Sepulveda in the Eastlake architectural fashion. The original construction included two commercial businesses and three residences. It has since and then go a preserved museum, and is cited past its website as a representation of the "blending of Mexican and Anglo culture".[eighteen]

Eloisa Martínez de Sepúlveda was born in the land of Sonora in Mexico. She lived there until 1844 when her parents, Francisca Gallardo and Estaquio Martinez, moved to Alta California at the urging of Francisca'due south brother, bringing the 11-yr-old Eloisa and her older brother Luis, with them to Los Angeles. In 1847, Señora Francisca Gallardo received from the ayuntamiento (Mutual Council) a plot of country between Bath and Wine street (renamed Olvera Street in 1877) on which she constructed an adobe residence. Señora Gallardo'southward adobe home at number 12 Bath Street was later enlarged to include by 1870 a second story and hipped roof. When Eloisa married Joaquin Sepulveda at the age of 23, she brought with her a dowry of land and cattle. Joaquin was an undistinguished member of an illustrious Southern California family unit. The spousal relationship suffered from misfortune as the couple's only child died in infancy and Joaquin himself died in 1880 leaving no property. Señora Gallardo gave her property to her widowed girl, Eloisa Martinez de Sepulveda, in 1881. On lands owned by her mother, Eloisa was able to finance the construction of a commercial building which provided her with a steady income. This was the Sepulveda Block, congenital in 1887.

Señora Eloisa Martinez de Sepulveda congenital the two-story Sepulveda Block in 1887 in response to the city's real manor and population boom of the 1800s. The twenty-ii room building toll $8,000 to erect. As her husband, Joaquin Sepulveda, had died vii years earlier leaving no estate, Señora Sepulveda probably financed the structure of the edifice on her own. Past 1888 Bath Street had been renamed Main Street and the city had realigned and widened it, cutting off eighteen anxiety (5.5 grand) from the front of the adobe. Señora Sepulveda received $1,190 in compensation.

When the Sepulveda Block was built in 1887 Señora Eloisa Sepulveda kept a suite of three rooms for her own utilise. Her sleeping accommodation reveals much about her Mexican heritage and the popular tastes and styles of the time. It would likewise reflect some of the places in Los Angeles in the decades following her arrival from Sonora in 1844. The décor of the room shows a practical acceptance of modern engineering science and contemporary fashion, with its mass-produced walnut piece of furniture and gaslight chandelier. The bedroom has three dissimilar wallpapers and a typical flowered carpet. The somewhat cluttered appearance is feature of the period and a sign of modest prosperity. Past dissimilarity, the brass bed with its draperies and fancy spread, the Chinese shawl, and the well-tended shrine are representative of Señora Sepulveda's Mexican upbringing and her strong religious beliefs. The large crucifix is on loan from Señora Sepulveda'due south descendants while the bed belonged to the Avila family unit, who were related to her by marriage. The pastel portrait is of her favorite niece, Eloisa Martinez de Gibbs.

Señora Sepulveda chose American architects George F. Costerisan and William O. Merithew to design her two-story business concern block for residential and commercial rental in 1887. Although this detail blazon of building is probably unique in Los Angeles today, it was a "design book" edifice of a style that was common all over the land at the time. An exception in this edifice is the typically Mexican breezeway which separates the Main Street stores from the dwelling rooms in the rear. Thus, the Sepulveda Cake represents the transition in Los Angeles from Mexican to a combination of Anglo and Mexican styles. The piece of work "cake" is the Victorian term for a big commercial building. Past this fourth dimension the city had inverse from a Mexican pueblo with a cattle-based economic system to an American boondocks with an agronomical economy. The population had grown from less than 2000, most of whom were Mexican, to over 50,000, only 19% of whom were Mexican. When the building was synthetic it appears that Señora Sepulveda herself occupied the 3 residential rooms located in the rear, facing Olvera Street, so an unpaved aisle. Later, she may have occupied other quarters. Commercial tenants were located in the stores fronting on Main Street while the 2nd floor was used as a boarding house.

Señora Sepulveda bequeathed the edifice on her death in 1903 to her favorite niece and goddaughter, Eloisa Martinez de Gibbs. Edward Gibbs, an engineer and lumber company owner, had been a tenant in the Sepulveda Cake. In 1888, the same twelvemonth that he and Eloisa were married, Edward was elected to the City Council. Four of their five children were born in the second floor facing Master Street on the south side. In 1905, along with many other residents of the area, the Gibbs moved to a more fashionable neighborhood in Los Angeles. Succeeding generations of the Gibbs family unit operated the Gibbs Electrical Company and retained buying of the Sepulveda Block until it was acquired by the State of California for $135,000 in 1958 as part of the Pueblo de Los Angeles State Historic Monument.

Between 1982 and 1984 major restoration took place in the Sepulveda Cake. The edifice was structurally stabilized and plumbing, heating, air conditioning and electrical systems were installed. A new roof replaced the old 1 and the front staircase, which had been removed in the 1930s, was put back. The iron cresting is restored as are the blood-red tin can tiles over the bay windows. The w façade is "penciled" in the style of the menstruum, meaning that the bricks are painted and mortar lines are traced in white on superlative. The due east façade on Olvera Street, although not originally painted, had previously been sandblasted, a process which destroys the outer surface of the brick, making it porous. Every bit paint provides bricks with protective coating, they have been painted with the color which was start used in 1919. A 1983 archeological excavation beneath the wooden floor unearthed artifacts relating to the building's history. Peter Snell, partner with Long Hoeft Architects and Gus Duffy Architect, were the firms responsible for the Sepulveda Block restoration plans and structure supervision.

During Globe State of war II the Sepulveda Block became a canteen for servicemen and three Olvera Street merchants were located in the building. The edifice continued to exist used by Olvera Street merchants until 1981 when they were relocated for the building'due south restoration. Today, El Pueblo Park's Visitor's Center is located in the south store on the ground flooring. This room represents the Victorian Eastlake style of 1890. Restoration plans call for the creation of an 1890s grocery shop on the north side of the first floor.

Mural América Tropical [edit]

The mural América Tropical (full name: América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos, or Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed past Imperialism,[19]) by David Siqueiros, was unveiled in a higher place the street in 1932. It was shortly covered upwards to mask its political content. The Getty Conservation Constitute has performed detailed conservation piece of work on the mural to restore it and the America Tropical Interpretive Heart opened to provide public access.[20]

Plaza Substation [edit]

The Plaza Substation, also at 10 Olvera Street, was part of the electric streetcar system operated past the Los Angeles Railway. Completed in 1904, the substation provided electricity to power the yellow streetcars. When the streetcar arrangement closed in the 1940s, the edifice was converted to other uses. The substation is one of the ii buildings in the district that is separately listed in the National Register of Historic Places (the Avila Adobe is the other).

Pelanconi House [edit]

Pelanconi House at 17 Olvera Street, built in the 1850s, is the oldest surviving brick house in Los Angeles.[21] In 1924, it was converted into a eating house called La Golondrina, which is the oldest restaurant on Olvera Street.[22] The Pelanconi Firm was a winery producing wine from the grapes that grew in the area, maybe even inside the Avila Adobe where they abound currently. The DNA matches that of grapes at Mission San Gabriel, established in 1771.[23]

Plaza Methodist Church [edit]

Built in 1926, the Plaza Methodist Church was built in 1926 on the site of the adobe once owned past Agustín Olvera, the man for whom Olvera Street was named. It is at the southeast corner of Olvera Street and Paseo de la Plaza (i.e. the Plaza).

Eugene Biscailuz Building [edit]

The former United Methodist Church headquarters, besides congenital in 1926, was renamed in 1965 for Sheriff Eugene West. Biscailuz, who had helped Christine Sterling to preserve and transform Olvera Street. It housed the Mexican Consulate until 1991 and then the Mexican Cultural Institute.[24]

Buildings on Primary Street [edit]

Gallery (west side) [edit]

Gallery (east side) [edit]

Pico House [edit]

Pico House was a luxury hotel built in 1870 by Pío Pico, a successful businessman who was the last Mexican Governor of Alta California. With indoor plumbing, gas-lit chandeliers, a grand double staircase, lace curtains, and a French restaurant, the Italianate three-story, 33-room hotel was the most elegant hotel in Southern California. It had a full of virtually eighty rooms. The Pico House is listed every bit a California Historical Landmark (No. 159).

Masonic Hall [edit]

Masonic Hall at 416 Due north. Main St., was congenital in 1858 every bit Social club 42 of the Free and Accepted Masons. The building was a painted brick structure with a symbolic "Masonic middle" below the parapet. In 1868, the Masons moved to larger quarters farther south. Afterward, the building was used for many purposes, including a pawn shop and boarding business firm. It is the oldest edifice in Los Angeles south of the Plaza.

Merced Theater [edit]

The Merced Theater, completed in 1870, was congenital in an Italianate style and operated as a live theatre from 1871 to 1876. When the Forest Opera House opened nearby in 1876, the Merced ceased being the city'southward leading theatre.[25] Eventually, it gained an "unenviable reputation" because of "the disreputable dances staged there, and was finally closed past the regime."[26]

Plaza House [edit]

This two-story building at 507–511 Northward. Main St. houses office of the LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, which includes the Vickrey -Brunswig Edifice next door.[27] Information technology is inscribed on its upper flooring, and on 1890s maps it is marked, "Garnier Block" (non to be confused with the Garnier Block/Edifice on Los Angeles Street, one block away). Commissioned in 1883 past Philippe Garnier, once housed the "La Esperanza" bakery.[28]

Vickrey-Brunswig Building [edit]

This five-story brick building facing the Plaza at 501 N. Primary St. houses LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, which besides occupies the Plaza House next door. It was congenital in 1888 and combines Italianate and Victorian architecture; the architect was Robert Brown Young.[29]

Site of Sentous Building [edit]

The Sentous Block or Sentous Edifice (19th c., demolished late 1950s) was located at 615-9 Due north Main St., with a dorsum entrance on 616-620 North Spring St. (previously called Upper Main St., then San Fernando St.). Designed in 1886 by Burgess J. Reeve. Louis Sentous was a French pioneer in the early days of Los Angeles.[thirty] The San Fernando Theatre was located here. The site is now part of the El Pueblo parking lot.[31] [32]

Buildings on Los Angeles Street [edit]

-

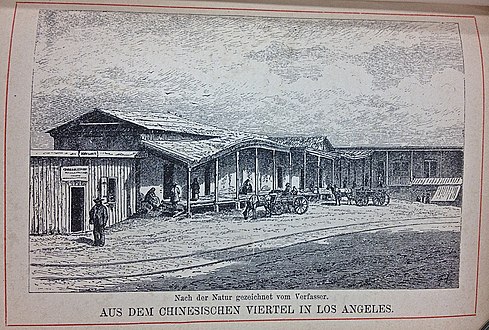

Old Chinatown stretched from Sanchez Street across Los Angeles Street to what is now Union Station. c.1885.

-

Lugo Adobe lining the eastern edge of Los Angeles Plaza. The street in forepart of the adobe was office of Los Angeles St. starting in the 1880s.

-

1882 view, looking due north from Broad Place along Calle de los Negros to the Ignacio Del Valle adobe in the far background. At left, with the peeling paint, is the Coronel Adobe (SE corner of Arcadia). A few years afterward, both adobes would be demolished and Los Angeles St. would be extended due north to (and past) the Plaza.

-

Looking east on Arcadia towards houses lining the e side of Broad Place. Aliso Street runs class their correct side towards the background. Calle de los Negros runs to the left in front of them. The Coronel Adobe is at left.

-

-

2005 view. Brick buildings at eye-left are at the south end of the Plaza. Los Angeles St. runs along the Plaza's right (east) side, southward towards the eastern edge of Los Angeles Mall (lesser center). The circular cluster of trees and freeway onramp to the right of the Plaza is the Lugo Adobe site. Behind them is Union Station.

Northern end of Los Angeles Street [edit]

In 1888, Calle de los Negros had just been renamed, and hither is marked Los Angeles Street (only the section from Arcadia to the Plaza). In that same year, only non however reflected on the map, the Coronel Adobe would be removed to allow Los Angeles Street to continue straight north to the Plaza from Wide Place.

The Colonel Adobe was demolished in 1888 and 1896 Sanborn maps show that the Del Valle adobe had been removed, and Los Angeles Street had been extended[33] to class the eastern edge of the Plaza, thus passing in front of the Lugo Adobe. Calle de los Negros remained for a few more decades, behind a row of houses lining the e side of Los Angeles Street betwixt Arcadia and Aliso streets. This was also the western edge of Old Chinatown from around the 1880s through 1930s. It reached e across Alameda St. to encompass nearly of the surface area that is now Marriage Station. It proceeded one more block past the Plaza, with the buildings on the eastward side of Olvera Street forming its western edge, until terminating at Alameda Street.[34]

Eastern edge of Plaza [edit]

Since the early on 1950s, Los Angeles Street has formed the eastern edge of the Plaza, but the buildings lining its eastern edge, including the Lugo Adobe, were removed.[35] [36] The site is now Male parent Serra Park.

From the Plaza northward to Alameda [edit]

Placita Dolores, where from 1888 until the 1950s, Los Angeles Street used to run a short block due north of the Plaza to terminate at Alameda St.

When it was extended past the Plaza in 1888,[33] Los Angeles Street terminated 1 short block n of the Plaza at Alameda Street. Now, Los Angeles Street turns east at the n side of the Plaza to terminate at Alameda Street at a right angle, direct across from the Union Station complex. What was the short block of Los Angeles Street northward of the Plaza is now part of Placita Dolores, a pocket-size open plaza which surrounds a statue of Mexican charro entertainer Antonio Aguilar on horseback.[37]

Calle de los Negros [edit]

Until the late 19th century, Los Angeles Street did non form the east side of the Plaza; information technology ran south only from Wide Place at the intersection of Arcadia Street. Here, the Coronel Adobe blocked the path northward 1 block to the Plaza, but simply slightly to the right (east) of the path of Los Angeles Street was Calle de los Negros (Castilian-linguistic communication name; marked on post-1847 maps equally Negro Alley or Nigger Aisle), a narrow, one-block north–due south street likely named afterward darker-skinned Mexican afromestizo and/or mulatto residents during the Castilian colonial era.[38] [39]. At the north terminate of Calle de los Negros stood the Del Valle adobe (also known as the Matthias or Matteo Sabichi firm),[40] [41] at the southern edge of which one could plough left and enter the plaza at its southeast corner. Calle de los Negros was famous for its saloons and violence in the early days of the town, and past the 1880s was considered function of Chinatown, lined with Chinese and Chinese American residences, businesses and gambling dens.[42] [43]

The neglected dirt alley was already associated with vice by the early 1850s, when a bordello and its owner both known as La Prietita (the night-skinned lady) were agile here. Its other businesses included malodorous livery stables, a pawn shop, a saloon, a theater and a connected restaurant. Historian James Miller Guinn wrote in 1896, "in the flush days of gold mining, from 1850 to 1856, it was the wickedest street on earth...In length it did not exceed 500 feet, but in wickedness, it was unlimited. On either side it was lined with saloons, gambling hells, dance houses and disreputable dives. Information technology was a cosmopolitan street. Representatives of different races and many nations frequented it. Here the ignoble crimson man, crazed with aguardiente, fought his battles, the swarthy Sonorian plied his stealthy dagger, and the click of the revolver mingled with the clink of golden at the gaming table when some chivalric American felt that his word of "honah" had been impugned."[38]

By 1871, the alley was notorious as a "racially, spatially, and morally disorderly place", according to historian César López. It was hither that a growing number of Chinese immigrant railroad laborers settled after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. In that location, William Estrada notes, the "Chinese of Los Angeles came to fill up an important sector of the economy every bit entrepreneurs. Some became proprietors and employees of modest paw laundries and restaurants; some were farmers and wholesale produce peddlers; others ran gambling establishments; and some occupied other areas left vacant by the absence of workers in the gold rush migration to California." The Chinese population increased from 14 in 1860 to almost 200 by 1870. Guinn stated that the aisle stayed "wicked" through and afterwards its transition to the city'south Old Chinatown.[38]

Calle de los Negros was reconfigured in 1888 when Los Angeles Street was extended north, with a small, shallow row of houses remaining betwixt the new section of Los Angeles street's eastern edge and the western edge of the new, shortened aisle.[33] [44] The site of Calle de los Negros is now the Pueblo parking lot and a cloverleaf-manner archway to the United states of america 101 freeway.

Coronel Adobe [edit]

The Coronel Adobe was built in 1840 past Ygnacio Coronel every bit a family home. It stood at the northwest corner of Arcadia Street and Calle de los Negros; Los Angeles Street terminated at its southern end. The area gradually became an expanse for gambling and saloons, and upper-class families left to live elsewhere. Around 1849, they sold the business firm to a "sporting fraternity", which operated a popular 24-hour gambling institution with games including monte, faro, and poker; up to $200,000 in gold could be seen on the tables at a fourth dimension. Arguments ensued and murders were frequent. The building later became a dance hall where "lewd women" were employed, aimed at the Mexican-American population. After that, nonetheless in the 1850s, it became a grocery and dry out goods store (Corbett & Barker), then a storage house for iron and hard lumber for Harris Newmark Co. Information technology was then leased to a Chinese immigrant. In 1871, it was the site of the Chinese massacre of 1871. The Adobe was torn down in 1888 in order to extend Los Angeles Street n past the Plaza.[33]

Garnier Building [edit]

At 419 N. Los Angeles Street, at the northwest corner of Arcadia, is the Garnier Edifice, built in 1890, part of the city's original Chinatown. The southern portion of the building was demolished in the 1950s to brand way for the Hollywood Thruway. The Chinese American Museum is at present located in the Garnier Building. It should not exist dislocated with another Garnier Block/Building on Chief St. a cake away at present usually known as Plaza House.

Historical Mural painting [edit]

Various historical events of Los Angeles are depicted in a colourful trompe-50'œil mural painting.

Part of historic trails [edit]

Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail [edit]

The Pueblo de Los Ángeles is participating site of the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, a National Park Service area in the United States National Trails System. A driving bout map and listing of sites past County tin be used to follow the trail.[45]

Erstwhile Spanish National Historic Trail [edit]

The Pueblo de Los Ángeles was the terminal destination of the Old Spanish Trail. It is a site on the Onetime Castilian National Celebrated Trail, which was established in 2002. This historic trail does not nonetheless take designated visitor facilities or services. But museums, historic sites, and markers forth the Old Spanish Trail identify sites from Santa Fe to Los Angeles. The popular National Park Passport Stamps program is available at many sites along the trail, including the visitor middle of the Avila Adobe.

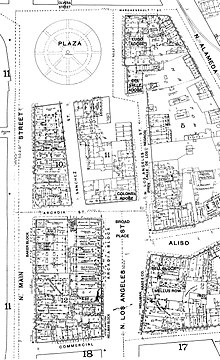

Celebrated map [edit]

Below is a map of the Plaza area with streets and monuments marked as they appeared in the 1880s.

Abbreviations and notes [edit]

- Italics indicate buildings that are nevertheless standing.

- Buildings non in italics were demolished.

- A dagger (†) indicates a street that no longer exists, or the pedestrianized areas, formerly considered streets on the perimeter of and at present considered part of the Los Angeles Plaza.

- "Female boarding" was a euphemism for small rooms, "cribs", used by prostitutes.[46]

*now Cesar Chavez Ave. **afterward Dusk Bl., Now Paseo Luis Olivares

| SHORT/BELLEVUE/SUNSET* | Sentous Block (1886–1950s) | M A I N Southward | MACY | L O S A Southward | MACY | A L A M E D A S | MACY | ||||

| Upper Main St. (San Fern- ando St., North Bound St.) | Pelanconi House (1850s) La Golondrina eating house (1924– ) Sepulveda House (1887) | O 50 V Eastward R A Southward | —Avila Adobe (1818) —Plaza Substation (1905) —Olvera Firm (19th c.)/ —Methodist Church and Eugene Biscailuz Bldg. (1926) | "Female person Boarding" | Orphan Asylum APABLAZA ST. Old Chinatown Now Spousal relationship Station (1939) | ||||||

| MARCHESSAULT ST.†** | MARCHESSAULT ST.† | MARCHESSAULT† | MARCHESSAULT† | ||||||||

| —Our Lady Queen of the Angels Church (1814/1861) Plaza House (1883) —Vickrey-Brunswig Bldg (1888) | LOS ANGELES PLAZA | —Lugo Adobe (1840s-1951) | Chinese theater | Old Chinatown At present Marriage Station | |||||||

| Del Valle adobe (?-1880s) | "Female boarding" | ||||||||||

| SONORA/REPUBLIC† | PLAZA STREET† | FERGUSON† | SHAFER† | ||||||||

| Hoffman Firm (hotel) | Carrillo House (1821-1869)/ Pico Firm (1875) Merced Theater (1870) | S A N C H East Z | —Chinese American Museum in the Phillipe Garnier Bldg.(1890) At corner: —Coronel Adobe (1840-1888)/ —Hotel King of beasts D'Or in Jeanette Block | Calle de los Negros —"Female Boarding" —"Chinese Quarters" Wilcox Bldg./ —Hotel Grenoble/ —Hotel De Gap Now parking lot and freeway onramp. | —"Female Boarding" —Hotel de France Now Wedlock Station complex. | ||||||

| Now Us 101 | ARCADIA now Arcadia St. & United states-101 | ALISO now Arcadia/US-101 | |||||||||

Encounter also [edit]

- List of Registered Historic Places in Los Angeles

- History of Los Angeles

- Fort Moore Pioneer Memorial

- LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes

- Mariachi Plaza

- Pueblo de Los Angeles

References [edit]

- ^ "National Register Information Arrangement". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "Roots of El Pueblo: The Get-go of Los Angeles". YouTube. 2018-12-13. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2020-11-26 .

- ^ "History". COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES. 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2020-10-12 .

- ^ "Ethnographic Overview of the Los Angeles Wood". Northwast Economic Associates: 101–104. 6 February 2004.

- ^ "History of the Los Angeles River". City of Los Angeles Department of Public Works.

- ^ "The Metropolis's Growth: Marching from the Old Toward the New Plaza; The Business organization Section Being Forced to the Southwest". Los Angeles Times. 1891-12-13.

- ^ a b "El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument". University of Southern California.

- ^ Ray Hebert (1970-06-08). "Plan to Commercialize Old Plaza Causes Rift: El Pueblo Park Agency Split on Lease Proposal". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ray Hebert (1982-08-01). "Historic Park; New Funds Spark Life in El Pueblo". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ruscin, p. 49

- ^ Los Angeles Department of Urban center Planning (September 7, 2007). "Historic - Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing: Urban center Declared Monuments" (PDF). City of Los Angeles. Retrieved 2008-05-29 .

- ^ Los Angeles #144 California State Parks Role of Historical Preservation

- ^ Judson Grenier. "Plaza Firehouse Centennial" (PDF). Los Angeles Public Library.

- ^ a b Miranda, Carolina (June 20, 2020). "At Los Angeles toppling of Junipero Serra statue, activists want full history told". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Los Angeles Plaza Park". City of Los Angeles Section of Recreation and Parks. Retrieved ii August 2014.

- ^ "Lugo, Vicente, Adobe, El Pueblo de Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, Pacific Coast Architecture Database

- ^ California, California Country Parks, Country of. "AVILA ADOBE". ohp.parks.ca.gov . Retrieved 2016-11-25 .

- ^ "Sepulveda House : El Pueblo De Los Angeles : The Metropolis of Los Angeles". elpueblo.lacity.org. Archived from the original on 2016-12-twenty. Retrieved 2016-11-25 .

- ^ Del Barco, Mandalit. "Revolutionary Mural To Return To L.A. Subsequently 80 Years", NPR, 26 October 2010. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Hernandez, Daniel (September 22, 2010) " 'America Tropical': A forgotten Siqueiros mural resurfaces in Los Angeles [Updated]", Los Angeles Times

- ^ "Restoration of Pelanconi House" (PDF). Los Angeles Public Library.

- ^ "La Golondrina" (PDF). Los Angeles Downtown News. 1995-11-xiii.

- ^ Virbila, S. Irene (September 18, 2015). "What to exercise with grapes from 150-year-old vines at Olvera Street? Make vino, of form". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ p. 112-three, Jean Bruce Poole, Tevvy Brawl, El Pueblo: The Historic Centre of Los Angeles, Getty Conservation Institute et al., 2002, ISBN 9780892366620, 0892366621

- ^ Lois Ann Woodward (1936). "Merced Theater" (PDF). Country of California, Section of Natural Resources.

- ^ Rose 50. Ellerbe (1925-x-25). "City's Progress Threatens Aboriginal Landmarks: Structures In one case City's Pride Now Hidden in Squalor". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Plaza House", Library of Congress

- ^ "Plaza House", Water and Power Associates

- ^ "LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, Vickrey-Brunswig Building", Los Angeles Conservancy

- ^ Louis Sentous biography, Bridge to the Pyrenees

- ^ "San Fernando Theatre", Los Angeles Theatres

- ^ plate 003 of the 1910 Baist Existent Estate Survey

- ^ a b c d "An Historic Edifice: Torn Downwardly to Brand Fashion for a Street: Reminiscences of the Past: History of the Movement to Open Los Angeles Street to Alameda". Los Angeles Herald. January 13, 1888.

- ^ Sanborn map of Los Angeles, 1894, plate 12, right half, lower correct

- ^ "End of an Era". Los Angeles Times. Feb 7, 1951. p. 31.

Cease OF AN ERA This is the old Lugo House on Los Angeles St., facing the Plaza, mainstay of xix buildings which will be torn down, outset today, to articulate the area between Union Station and the Plaza. Some say the Lugo House was begun in 1811. Once information technology was a magnificent dwelling, after it became the center of the pueblo's social life and now, after -years of disrepair, it volition die despite efforts of historical societies to save it.

- ^ "Wreckers Get to Lugo House and eighteen Other Ancient Abodes". Los Angeles Times. February 7, 1951. p. 31.

- ^ Zavis, Alexandra (September 17, 2012). "Los Angeles unveils statue of Mexican singer-histrion Antonio Aguilar". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c Lopez, Cesar. "Lost in Translation: From Calle de los Negros to Nigger Alley to North Los Angeles Street to Identify Erasure, Los Angeles 1855–1951" (PDF). Southern California Quarterly. 94 (1 (Spring 2012)): 39–40.

- ^ Beherec, Marc (2019). "John Romani'southward Forgotten 1984 Excavations at CA-LAN-007 and the Archeology of Native American Los Angeles" (PDF). SCA Proceedings. 33: 155. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- ^ Los Angeles' Piddling Italy, p.12

- ^ Marc A. Beherec (AECOM), "John Romani's Forgotten 1984 Excavations at CA-LAN-007 and the Archæology of Native American Los Angeles", Social club for California Archaeology, pp.155 ff.

- ^ vol. 1, Sheet 12_a, Sanborn 1888 map of Los Angeles (Metropolis), via Los Angeles Public Library

- ^ "Los Angeles…1850" (map), UCLA map collection via Online Annal of California

- ^ Sanborn 1894 map of Los Angeles, vol. 1, canvass 14b

- ^ Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, National Park Service. Accessed ix/ix/2010

- ^ Hadley Meares, "Hell's Half Acre: In the erstwhile cherry lite district of Los Angeles, women worked in squalor while pimps and landlords grew rich", Curbed L.A., November 17, 2017

External links [edit]

- El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument - official site

- Las Angelitas del Pueblo: The Docents of El Pueblo de Los Angeles

- The Olvera Street website

- official National Park Service Juan Bautista de Anza National Celebrated Trail website

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Pueblo_de_Los_%C3%81ngeles_Historical_Monument

0 Response to "From Her Art Exhibit 2019 El Pueblo De Los Angeles"

Post a Comment